2.4 The need for source criticism: three case studies

Challenges in researching objects, text carriers and texts

Source criticism, i.e. judging the value and reliability of objects, text carriers and texts for an investigation, is of major importance for two reasons:

- The sources functioned as utilitarian objects in memoria, so they were adapted if that was considered useful.

- As with all medieval sources, the ravages of time and human intervention may have altered their outward appearance and their value as a historical document.

For memorial pieces photos are not usually the most suited means of detecting alterations in the representation, just like photos cannot always be used to determine for inscriptions on tomb monuments and floor slabs whether they were added during the production of the slab, or much later. Another problem is that the polychromy of many objects has been lost: tomb monuments, floor slabs and memorial sculptures were multi-coloured, as were the frames of painted memorial images. Not only does this change the outward appearance of the objects, but it also means that texts, heraldry and important symbols have been lost. Damage and loss of (often important) parts of the objects may hamper research as well.

For text carriers it is sometimes easy to ascertain that pages or entire parts have been lost. In other cases extensive codicological research is required to detect alterations. If a text carrier contains multiple texts, it is important to know how these manuscripts have come about, because that knowledge may contribute to an understanding of the functioning of the separate texts. Text carriers containing multiple texts can roughly be divided into two variants, with a broad range of intermediate forms (see Gumbert, ‘Codicologische eenheden’). The MeMO project has chosen to follow the binary model and to provide additional information that allows for a more detailed understanding of the nature of the manuscript. The database distinguishes between the following:

- miscellanies: manuscripts containing multiple texts that show coherence in their themes or contents and/or that originate from the same institution. A miscellany may contain texts that all concern the commemoration of the dead. These manuscripts may have been copied as a whole for the institution where they were used. The texts in the text carrier, for instance a list of grave owners or a donations register, may have subsequently been kept up to date over a longer period, but the manuscript may also have been extended with new texts.

- composites: manuscripts containing texts that were conjoined at a certain moment in time, without necessarily sharing a theme or originating from the same institution. The texts in such a manuscript were usually bound together on the basis of the sizes of the separate parts (texts). There does not need to be any cohesion between the texts in a composite; besides memorial texts it may also contain profane texts in the same binding. This type of manuscript was often produced by order of a later owner.

The following sections discuss three cases, each with their own challenges.

1. The ‘Chapter Book’ (kapittelboek) of Berne Abbey

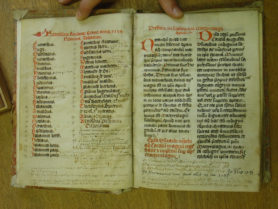

Fig. 8. List of the abbots of the Norbertine abbey of Berne. The list of abbots until 1574 was copied as a whole. The succeeding abbots were added afterwards, with numbers to ensure that the order of succession would be remembered correctly, MeMO text carrier ID 17

Berne Abbey kept a miscellany that is known as a ‘Chapter Book’ (kapittelboek). These kapittelboeken usually contain texts that were used in the liturgy of the chapter, the daily meeting of the conventuals in the chapter house (see fig. 8). The kapittelboek of Berne Abbey contains two memorial registers. One of these is a list of names (succession list) of abbots, the other is a calendar with memorial services to be performed, which is simultaneously a list of donations. There are similar kapittelboeken from other Norbertine monasteries, some of which, like the Berne manuscript, contain a calendar. Its presence in this Norbertine abbey was therefore not unusual, but the moment and manner of production of the manuscript raises all sorts of questions.

The manuscript was copied as a whole by Arnoldus van Vessem (1549-1608) in 1574. The old kapittelboek may have had to be replaced due to extensive use, but that is probably not all. The manuscript was produced when the conventuals were ‘in exile’. They had been expelled from their abbey in 1572 and the group has become dispersed over several monasteries. Only in 1623 did the Berne conventuals receive a residence of their own again, in Den Bosch.

Clearly then, the kapittelboek played no part in the liturgy of the abbey. The copying of the manuscript may have had other functions, however – especially in these trying times. It may have been an expression of the faith in the future recovery of the community of the living and the dead in their own abbey. The recording of the donations may also have functioned to produce a survey of (parts of) their legal assets.

Besides the questions as to the functions and meaning of the manuscript there are also the questions as to how it was produced. Is it an integral copy of the abbey’s old kapittelboek, and did that one contain the same texts as the miscellany of 1574, or did Arnoldus van Vessem compile it from several different documents?

The list of abbots’ names provides no clues here. It was customary to create a succession list of the superiors of monasteries and convents, and it is very well possible that Van Vessem copied the list as a whole in 1574. He may however have corrected and amended it. The only thing that we know is that it was added to regularly after 1574 (fig. 8).

It has been established that Van Vessem used one or more older registers that have since been lost for composing the calendar. This fact has been established from the mention of Norbertine nuns from the twelfth century. Their names are mentioned without any mention of the convent that they had entered, indicating that they came from Berne Abbey. Founded in 1134, it used to be a double monastery (for both men and women) in its early stages. This is what we know, but for now it is impossible to say whether or not the 1574 register provides a full survey of the deceased conventuals from the early stages.

Without exhaustive research there remain many questions on how Arnoldus van Vessem produced the manuscript of 1574. It is even possible that these questions may never be resolved.

2. The memorial sculpture of Joost Sasbout and Catharina van der Meer

Adaptations of memorial monuments such as tomb monuments, floor slabs and memorial pieces may have been made with special intentions in mind. If one is to say anything about the intentions of the patrons it is necessary to distinguish the original monument from the adapted one.

Fig. 9a. Memorial sculpture of Joost Sasbout († 1546), a high official first in Holland and later in Guelders, and his wife Catharina van der Meer († 1560) in the Grote Kerk in Arnhem. The religious image has not survived, nor have the wings that were attached on either side, MeMO memorial object ID 570

The Eusebiuskerk in Arnhem houses the memorial sculpture of Joost Sasbout (1487-1546) and his wife Catharina van der Meer († 1560, figs. 9a and 9b). The monument was probably produced by Colijn de Nole, based on stylistic characteristics and the type of stone used. It may have been commissioned by the commemorated persons.

The partially preserved monument consisted of three parts. Of the central part the relief with (probably) the Birth of Christ has been lost, as well as the wings, whose hinges however are still present. The upper part houses two sculptures of angels holding a book, which refers to the Incarnation of the Word. The lower part consists of two text plates and an image of two figures lying down, one a skeleton and the other a recently deceased woman.

In the literature on the memorial sculpture there has been a discussion since the nineteen eighties about the manner in which the monument was produced. Some authors conclude that the central part with its text in Gothic script is the original part. The lower part with the cadaver effigy and its inscription in Roman script and the upper part are thought to be of a later date. Arguments in favor of this conclusion are the sizes of the parts of the monument, which do not quite match, as well as the contrast between the traditional text on the central part (name and death date) and the humanist texts on the other parts.

Recent comparative research of floor slabs, tomb monuments and memorial pieces has shown, however, that the monument of Joost Sasbout and his wife may have been produced as a whole after all. Different aspects were involved in this investigation. It turned out that in the sculptures that have been attributed to Colijn de Nole on stylistic grounds there are more examples of different parts that do not quite match in size. Also, it is clear that combinations of traditional and humanist texts and scripts were not unusual in the Netherlands by the middle of the sixteenth century, see among others MeMO memorial object ID 233, circa 1535, and ID 1385, probably between 1524 and 1537.

Due to the lack of an image in the central part and on the wings, that possibly also bore images, the precise functions as intended by the patron or patrons of this memorial monument cannot be established anymore. It is self-evident that the memorial sculpture served to commemorate the persons mentioned. But Joost Sasbout, a high functionary in Guelders, and his wife may also have had other intentions with this complex monument and may have tried to convey a socio-political message to the beholders.

3. Two wings with (overpainted) devotional portraits

Over the past decade technological research and restorations of painted memorial pieces have brought a large number of sometimes centuries old alterations in the representation to light. The case study here is a work of art whose alterations can even be seen with the naked eye – that is, for those who can go and see the work of art for themselves, because even good photographs do not always provide sufficient information.

Fig. 10a. Wings with the devotional portraits of an unknown family and overpainted heraldry (1540-1545), MeMO memorial object ID 678

The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna holds two paintings with a number of as yet unidentified devotional portraits. Together with a painting in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam they probably constituted a triptych (figs. 10a and 10b). On stylistic grounds both the Rotterdam painting and the Vienna wings can be attributed with great certainty to the Haarlem painter Maarten van Heemskerck. It is easy to see with the naked eye (and even on a good photograph) that the heraldry on the wings has been painted over and replaced by other heraldry. The other intervention was discovered due to daylight skimming over the painted surface of the wings. Such so-called oblique or raking lighting conditions expose irregularities in the layers of paint.

For those who do not use this lighting it looks like there are only adults on the wings, two men on the left wing and four women on the right wing. Raking or oblique lighting has shown, however, that there are children on both wings, a boy on the left wing and a girl on the right one. It is still a mystery what is going on here. The artist clearly painted portraits that resembled the sitters; even the heads that can only be seen in raking light are real portraits. The adult portraits do not seem to have been altered, but technological research is required to confirm that. More research is also required in order to establish whether the alterations in the heraldry and the overpainting of the children’s portraits occurred simultaneously. Only then may answers be found on questions of the identities of the portrayed persons as well as the how and why of the alterations.

This is not a unique example. Portraits, heraldry and texts turn out to have been altered, painted over or removed, or to have been added to an already finished representation (see for instance MeMO memorial object ID 728, ID 748, ID 749 and ID 782). Sometimes it is clear that the alteration occurred when the painting was still functioning as a memorial piece. Why would one have a new memorial piece made for someone whose portrait would fit very well into a finished memorial piece, for instance among the portraits of his fellow brothers (MeMO memorial object ID 563). After all, such a piece shows the community of the deceased.

The importance of public access to research data

A sound source criticism is the basis of all historical and art historical research. That is why museums, archives and other heritage institutions increasingly publicise the results of technological and codicological research and of preservation and restoration, and will hopefully do so online increasingly often in the future. In this way researchers will be able to avoid pitfalls, and researchers of medieval memoria, for instance, will have a higher success rate in tracing the functions of the texts and objects in the commemoration of the dead.