3.4 Alterations and consequences

Some general points of interest to consider when researching memorial monuments

Today many floor slabs, memorial pieces, etc. look different from when they were produced or when they still had their original function. These changes are cause by:

- Climatological circumstances and pollution. Contraction and expansion of wood panels can cause the paint to peel off from a painting, thereby obscuring (parts of) the image or text. See MeMO memorial object ID 653.

- Wilful destruction of objects, e.g. the repeated iconoclastic attacks in the sixteenth century. See MeMO memorial object ID 496.

- Everyday use of objects: also in the Middle Ages floor slabs functioned as parts of the floor that people walked on, leaving signs of wear and tear. See MeMO memorial object ID 3658.

- Alterations due to desired changes in function. Heraldic shield or coats of arms, texts and portraits were added, removed or replaced (see MeMO memorial object ID 563 and chapter 2.4).

- Restorations (see fig. 8a and 8b).

Fig. 8a. Tomb monument of Gijsbrecht van Amstel van IJsselstein, Bertha van Heukelom, Arnold van Amstel van IJsselstein and Maria van Henegouwen in the Oude Sint-Nicolaaskerk in IJsselstein (ca. 1370). Situation before the restoration, see MeMO memorial object ID 1437

There are serious consequences. Large numbers of memorial sculptures look entirely different because the painting (polychromy) has been lost. Sometimes some remnants of the paint still show.

Fig. 8b. The same tomb monument after the restoration

Tomb monuments and floor slabs and the brasses that covered them could also be coloured, especially the effigies and the heraldry. The materials used were paint, coloured putty, inlaid stone (such as marble or alabaster), enamel, and precious or semi-precious stones. One would expect the heraldry arms to be painted, but it is unclear whether that was always the case. In a number of cases these objects still show traces of colour, see fig. 9.

Clearly the damages, alterations and loss of texts and painted images can create problems for researchers attempting to establish the intended and actual functioning of the objects.

Floor slabs and tomb monuments

Fig. 9. Detail of the effigy of the Utrecht bisschop Guy van Avesnes († 1317). The indents in his vestments and mitre show that the effigy was decorated, probably with glass and/or (semi)precious stones, see MeMO memorial object ID 2941

Creating the inventory and the descriptions of the tomb monuments and floor slabs has proved problematic in a number of ways. The point of departure were the inventories and descriptions by Bloys van Treslong Prins, Muschart, Belonje, etc. Their inventories have been of major importance for research into tomb monuments and floor slabs, but they are outdated. Problems encountered by MeMO:

- upon closer inspection inventories proved to be incomplete

- descriptions of tomb monuments and floor slabs were often incomplete or incorrect

Moreover, the inventories and the information provided are no longer always reliable:

- some of the monuments and slabs that were inventoried have been lost due to fire, wear and tear, and other types of destruction

- there are extant or possibly extant slabs that are now concealed (by wooden flooring or wall-to-wall carpeting), and these have not been photographed (in high quality).

Tomb monuments and floor slabs have often been moved. They may have been moved around inside the church of origin, or even have been transferred to other churches. In Utrecht there are a number of floor slabs that are located in a church that is not the church of origin, even if the original church still exists: at least eight slabs have been transferred from the Buurkerk to the Domkerk, and three have been moved from the Domkerk to the Janskerk. The transfers are usually the result of restoration projects that were carried out in the twentieth century. Among other things, this situation has consequences for determining the original function, which is often connected with the original location. Therefore, the information on the original institution as well as the original location within the institution, and on the functions of tomb monuments and floor slabs has been provided in the database with some reserve.

Progressive insights have also provided a caveat. For instance, the description of stone types has been made with caution, as these can usually only be determined on site after extensive research by specialists.

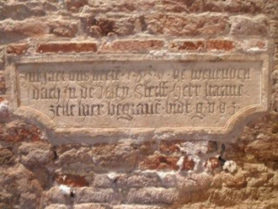

Fig. 10. Remnant of a memorial piece of Harmen Zelle, priest of the Bovenkerk in Kampen. The shape of this text tablet clearly shows that it originally belonged to a larger object, see MeMO memorial object ID 1841

Possible problems when researching memorial pieces

These days the memorial function of memorial pieces is easiest to recognise by the devotional portraits of deceased children in their long white or coloured gowns and, if the epitaph texts have survived, by the mention of the names and dates of death. These texts were inscribed on the frames of the paintings or on accompanying or attached text panels. The great majority of the texts and text panels have been lost, however. Even if the paintings are still in their original frames these have often been treated with lye, causing the paint layers and thus the texts to disappear. Many paintings have been given new frames, in the process of which the text panels that were affixed to the old frames were removed as well. Some original frames still show the holes that housed the wooden pins that affixed the text panels to the frame (see MeMO memorial object ID 626 and ID 633). The reverse is the case with memorial sculptures: they often retain the texts, but the images have usually been removed (see MeMO institution ID 19 and fig. 10).

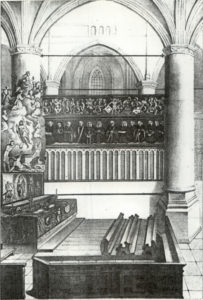

In memorial pieces the devotional portraits usually accompany a religious image. This is the reason why panels in which devotional portraits are the main image have been described in the database as wings of a larger whole. A caveat: panels with devotional portraits that may seem to have been wings may have functioned as independent paintings. In such cases the persons portrayed in the devotional portraits were not placed towards the religious scene in the image itself, but facing an altar or the choir with the altar, for instance, see fig. 11.

Fig. 11. Drawing of the Van Beveren chapel in de Grote Kerk in Dordrecht (ca. 1660). The memorial painting in the back shows the portraits of the Van Beveren family kneeling towards the altarpiece on the left. A fragment of the family portrait was discovered in 2019. Photo: RKD, The Hague

Present location unknown

Please keep in mind that the indication ‘present location unknown’ sometimes holds different meanings for memorial pieces on the one hand, and for tomb monuments and floor slabs on the other hand.

- For memorial pieces this usually means there is reason to assume the object still exists, but that it is either part of an unknown private collection, or part of a museum collection without a catalogue.

- For tomb monuments and floor slabs this indication means there is more uncertainty: they could be, as described above, destroyed, covered up, or relocated. Because not all objects could be examined in person or through (recent) photographs, and because recent literature isn’t always available, in some cases information from older, potentially not up-to-date literature was used.